Reviewed by a TELG attorney in June 2019

DISCLAIMER

This self-help guide provides general information about a legal process, but it is NOT legal advice upon which you should rely. Every case is unique and requires individual analysis. If you seek legal advice, please consult with an attorney. Use of this self-help guide, or of our firm’s Web site more generally, does not create an attorney-client relationship between you and The Employment Law Group® law firm. To arrange a consultation with our firm, please contact us.

WHAT’S IN THIS SELF-HELP GUIDE

Introduction

Do I Qualify to File a WPA Complaint at the OSC?

What Outcomes Can I Expect?

Getting Ready to File

Filling Out the Complaint Form

What Happens Next

The OSC Investigation Process

About Mediation

What if the OSC Closes My Case?

About The Employment Law Group

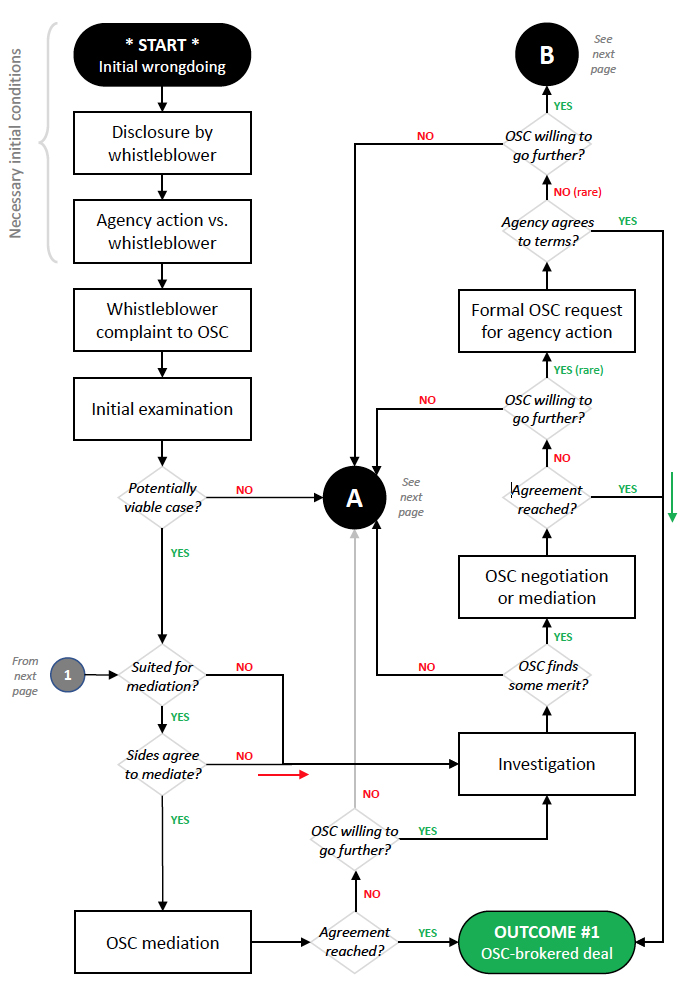

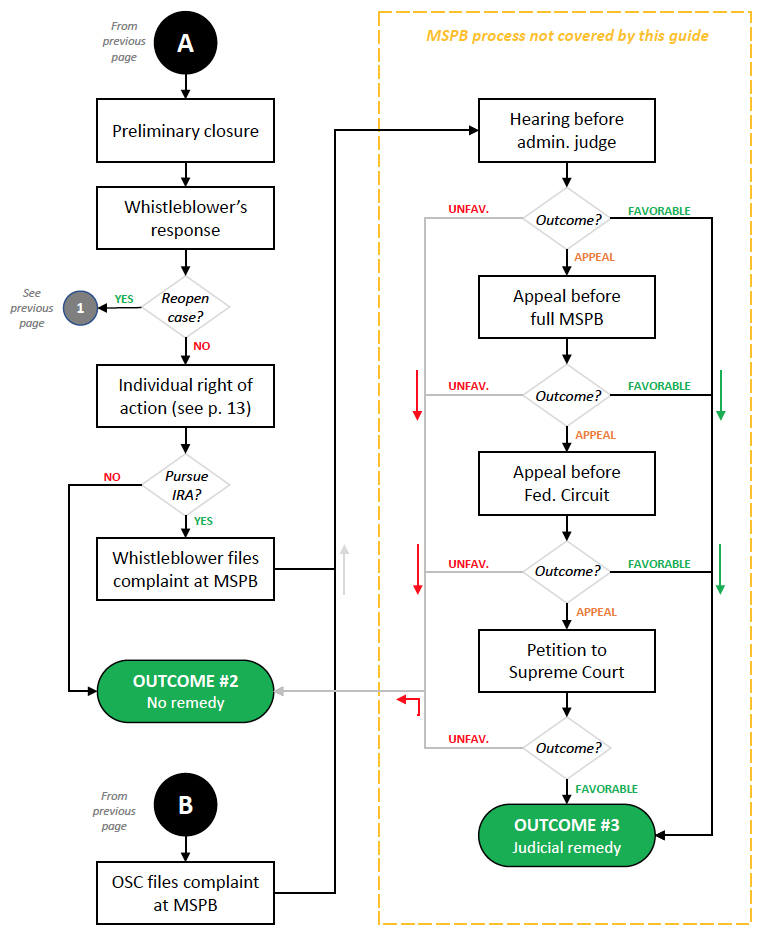

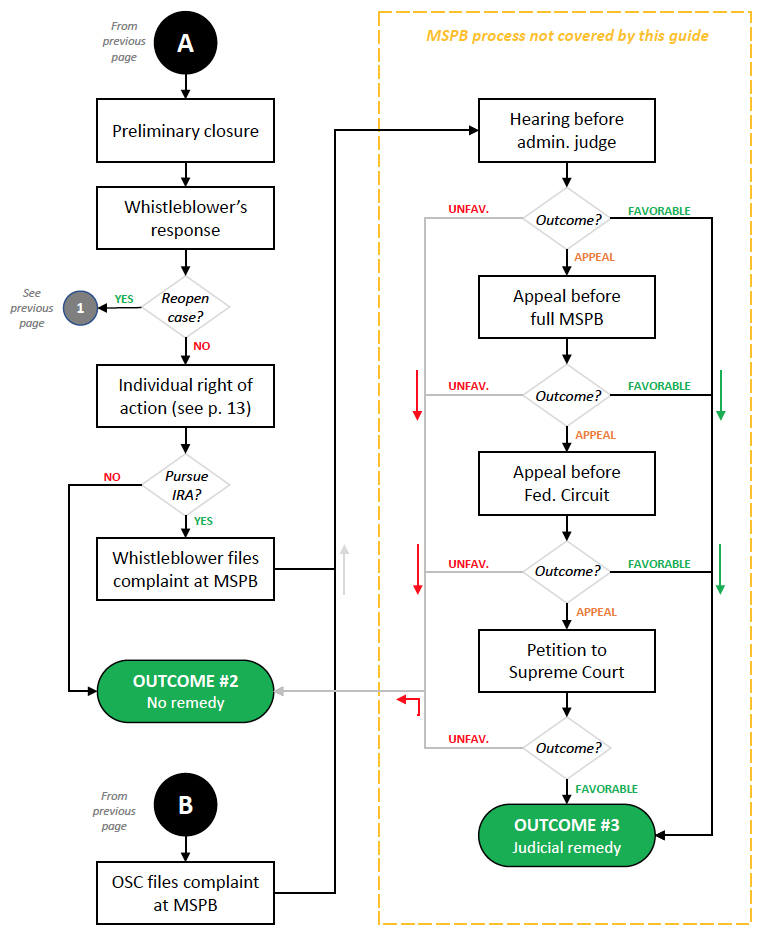

Appendix: Flowchart of the OSC Process

INTRODUCTION

The Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA) became law in 1989. It protects federal employees from retaliation for disclosing various sorts of wrongdoing at government agencies. The idea behind the law is simple: If whistleblowers don’t fear retaliation, they’re more likely to expose bad actors within the government. That’s good for everyone except the bad guys.

If you’re a federal employee who has been punished for speaking up—or even if you were punished because someone else spoke up—you can trigger the WPA’s provisions by filing a complaint with the Office of Special Counsel (OSC), an independent federal agency that’s charged with protecting whistleblowers under the WPA.

Be aware that you can seek justice in other ways, too:

- If your punishment is directly appealable to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB)—a removal or reduction in pay, for instance—you may skip the OSC and go straight to the MSPB; or

- If you’re represented by a union, you may be able to file a grievance.

This guide doesn’t cover the merits of those alternatives. In general, once you have selected one path the others will become closed to you.

If you decide to proceed via the OSC, an examiner will consider your complaint and the OSC may seek corrective action from your agency and/or bring your case before the MSPB. However, the OSC also may decline to pursue the matter. If that happens, you’ll have an option to continue to the MSPB without the OSC’s help. This is called an “individual right of action” (IRA).

The OSC allows whistleblowers to file complaints without hiring a lawyer, and many federal employees do so. Proceeding without a lawyer isn’t crazy, by any means, but it raises two big-picture concerns:

- First, a lawyer can guide you through the complex OSC process, where simple errors may result in your case being closed; and

- Second, the opposing side—your own department or agency—definitely will have the advice of its own lawyers.

Still want to go ahead by yourself? This guide will help you to set some realistic expectations.

DO I QUALIFY TO FILE A WPA COMPLAINT AT THE OSC?

Before you approach the OSC with a whistleblower retaliation complaint, you should confirm that you’ll survive its initial screening. A complaint that’s closed immediately is a waste of everyone’s time.

What matters here? Well, the WPA protects whistleblowing by many federal employees—but not all. In addition, the law has a specific definition of whistleblower retaliation.

Here are the basics:

First, you must be a current or former employee, or an applicant for employment, in the executive branch of the U.S. government—with some big exceptions that include the uniformed military, certain intelligence agencies, and the FBI.

The WPA does not protect whistleblowers outside the federal government: Those are shielded by laws such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and, for government contractors, the False Claims Act and the National Defense Authorization Act of 2013.

NOTE

This guide is about whistleblower retaliation complaints under the Whistleblower Protection Act. The Office of Special Counsel also has authority to investigate complaints under other laws. If you have several interlocking issues and are unsure whether the OSC is the right place to start, ask a lawyer or call the OSC at 202-804-7000.

There is no specific time limit for filing a retaliation complaint with the OSC. As a practical matter, however, the longer you wait the less likely you’ll succeed.

Second, you must credibly claim that you (or someone else, like a spouse or a friend) made a protected disclosure.

What’s a protected disclosure? In brief, you or someone else must have raised a red flag—in a way that became known to your bosses—about what the whistleblower reasonably believed to be one of these five things:

- A violation of law, rule, or regulation;

- Gross mismanagement;

- Gross waste of funds;

- An abuse of authority; or

- A substantial and specific danger to public health or safety.

Simple workplace arguments don’t count as whistleblowing, nor do policy disagreements. The WPA wasn’t written to protect employees from garden-variety bad management; someone must have complained about something that looks like illegal or dangerous behavior.

Third, following the disclosure, your agency must have taken a personnel action against you. Removal is a classic personnel action, but there are plenty of others under the WPA—a bad performance rating, for instance, or a failure to promote, or even a threat of negative action.

And fourth, you must be ready to prove that the action was motivated, at least in part, by your disclosure. Sometimes this link is pretty clear: You write an e-mail about corruption on Monday; on Tuesday you’re sent home on a bogus charge of misconduct. If the retaliation happens more than a year later, however, your complaint may not get much traction—especially if the agency can offer a “legitimate” reason for acting against you. In such a case, the OSC will likely need evidence such as e-mails, discussions, or witness statements that demonstrate the real, illegal motivation.

WHAT OUTCOMES CAN I EXPECT?

As with any legal process, no particular outcome is guaranteed.

However, if you’re a federal employee who complains of being punished for whistleblowing, the WPA makes two basic promises: Your complaint will be investigated and, if it’s found to be meritorious, you will be made whole.

Like many “make-whole” laws, the WPA doesn’t offer punitive damages: The goal is to put you back in the state you’d be in without any illegal retaliation.

If you were removed because of whistleblowing, it’s reasonable to ask to be reinstated with back pay. If you were downgraded or denied a promotion, you can ask for a step up plus back pay. If you were transferred to an inconvenient location, you can ask to be moved back.

If your punishment isn’t yet in effect, you can ask the OSC to seek a stay (ie, a delay) of the action—especially if you’d suffer “substantial” harm without such a delay.

Since it was amended in 2012, the WPA also allows compensation for any pain and suffering you may have endured because of whistleblower retaliation. And the offending agency may be told to pay your litigation costs—including attorney fees, if applicable.

The OSC asks employees to declare the remedy they’re seeking at the time of complaint, so think about what you really want.

GETTING READY TO FILE

At our law firm, filing a complaint at the OSC is never the first step, nor even the second. A complaint is akin to a declaration of war; before the bullets start flying, we want to get our troops and supplies into position.

We hope you’ll take the same approach.

In this section, we outline some basic ways to prepare for an OSC investigation. If you follow them, you’ll file a better complaint and be ready for all that follows.

Important: For most of the remainder of this guide, we assume that you’ve been punished for a whistleblower disclosure that you made yourself. Even if someone else made the original disclosure, however, the same basic advice will apply.

PRO TIP #1

Create a timeline that tracks every separate disclosure you made and every retaliatory action you faced. For each item, list the date, the specific people you told (or who retaliated against you), the high-level details, and the specific evidence you can use to prove it. Many people find an Excel spreadsheet useful for this purpose, but use whatever works for you. Keep updating the timeline as your case progresses: The OSC will be interested in personnel actions that happen after your complaint, too.

First, gather as much relevant documentation as possible. This may be as easy as saving or printing out the e-mails in which you disclosed your concerns about wrongdoing, plus all evidence of your subsequent punishment. If you have proof of the underlying bad deeds—the wrongdoing about which you expressed concern—save that also. If you want to report additional misdeeds to OSC, get that documentation, too. Keep everything in a safe place.

You may be concerned that it’s against the rules to take documents from the workplace. If so, please seek a lawyer’s advice; every case is different. As a general matter, courts have ruled that it’s OK for whistleblowers to take material that proves wrongdoing as long as they’re selective and don’t go overboard by, for instance, copying the contents of an entire hard drive when a few individual files would suffice.

Next, make sure you have gotten your agency’s official written explanation for any personnel action you received. Challenge facts and ask for more details if needed—and ask, too, about how you’re expected to resolve the matter. Be proactive but not combative. Follow the process. Do it all via e-mail and save the documentation.

Do any co-workers know what happened? You’ll want to name them as witnesses in your OSC complaint, so you likely should give them a heads-up. OSC investigations are supposed to remain confidential, and federal employees are required to share whatever facts they know. If your friends remember things differently than you do, it’s best to know this before they contradict your account in an investigation.

PRO TIP #2

Review the agency’s official justification for the action it took against you and prepare to defend yourself aggressively. You’ll need to convince the OSC (or subsequent tribunals) that the punishment was due at least in part to your whistleblowing. What evidence will you provide? A smoking-gun statement is great, but those are rare. Maybe your supposed offense was taking long lunch breaks, but your peers never faced such bogus discipline? Write down names and dates for comparable incidents, along with anything else that will be helpful. If you have documentation, save it. This can be a big part of the OSC’s investigation.

Now is also a good time to review your own personnel record—the whole thing, not just the punishment you received after whistleblowing. Do you have any other black marks that could hurt your credibility with OSC? Your agency may raise them, arguing that your latest discipline was part of a bigger problem. Think about how you can show that those incidents are irrelevant to your case.

Conversely, if you had a spotless record with excellent performance reviews, you should gather all that documentation. Sudden punishment after years of praise may help to convince the OSC that your agency acted in bad faith.

Finally, regardless of your past record, now’s the time to become an absolutely perfect employee. Don’t arrive late or leave early without permission. Do your work well and don’t miss deadlines. Don’t use work computers for personal business. Be quiet and restrained, even if you’re provoked. You’re about to trigger an investigation will annoy your bosses. They’ll be looking for excuses to punish you yet again. Don’t give them the satisfaction.

The form you’ll be submitting is known as OSC Form 11, “Complaint of Possible Prohibited Personnel Practice or Other Prohibited Activity.”

The OSC offers several ways to file Form 11, including via e-filing, fax, and mail. For employees who are filing without a lawyer, we recommend a two-step process:

- Download a PDF copy of the form and fill it out until you are completely satisfied; and then

- E-file your complaint online, using the filled-out PDF as a guide. (You’ll need to create an account on the OSC site.)

NOTE

This guide is about complaints that don’t involve classified information. If your complaint involves classified information, ask a lawyer for advice or call the OSC’s Disclosure Unit at 800-572-2249.

Also, this guide is focused on reporting whistleblower retaliation using OSC Form 11. If you also want the OSC to investigate the underlying fraud/waste/abuse (ie, what you were punished for reporting), you should consider filing OSC Forms 11 and 12. Form 12 will trigger a probe that is limited to the underlying matter. This guide doesn’t cover Form 12.

Save your working PDF copy and also the final complaint as you filed it online, which should be available for printing and saving immediately after you complete it. If possible, don’t do your OSC filing on a government-owned computer, at your work location, or while you’re on the clock.

Once you file your complaint online, you’ll be assigned a case number; use it in all future communication with the OSC.

OSC Form 11 is available as a PDF here: https://osc.gov/Resources/osc11.pdf

The OSC’s e-filing page is here: https://osc.gov/pages/file-complaint.aspx

Be sure to read over Form 11 several times before starting to fill it out. The questions are reasonably straightforward. Following are some things to consider as you work through the form.

Part 1 / Question 6 (Contact info): List your personal e-mail address, not a government one—and be sure it’s an address you’ll check daily. List only phone numbers that are personal to you. It’s fine to list your desk phone at work. Don’t bother listing a fax number.

Part 1 / Question 8 (Collective bargaining agreement): Your rights are not affected by your answer but note that if you already have filed a grievance in this matter via your union, the OSC won’t pursue your complaint. This is tackled more directly in Question 11.

Part 1 / Question 10 (Employment status): Your answer must not exclude you from OSC jurisdiction. Again, check the OSC’s list of excluded groups. If you’re unsure, consult an attorney or ask the OSC.

Part 1 / Question 11 (Other actions): If you check a box indicating that you’ve appealed your punishment to the MSPB or filed a grievance via your union, you may have waived your right to an OSC investigation. If you’re unsure whether you can proceed with Form 11, consult an attorney or ask the OSC. If you can’t proceed with Form 11 but believe the OSC still should investigate the wrongdoing that you were punished for disclosing, consider filling out OSC Form 12 instead. (Not covered in this guide.)

Part 1 / Question 12 (Official responsible for violations): Name the actual human being who was most responsible for the retaliatory action(s) you faced. Don’t write something vague like “my superiors” or “the agency.” If multiple people were involved, name every individual you believe can be shown to have actively participated in descending order of involvement. This is not a time to be shy.

Part 1 / Question 13 (Actions to report): Some whistleblowers have faced discrimination or other prohibited practices by the same bad actor(s) before they made a protected disclosure. If such actions were totally unrelated to your whistleblowing, it’s likely better to submit a separate complaint about the non-retaliatory stuff. Keep your narrative as simple as possible. If you’re not reporting actions related to your whistleblowing, skip directly to Part 2 of the form.

If your protected disclosure was about earlier prohibited practices against you, however, fill out Questions 13-15. Here’s an example: Let’s say your supervisor denied you a promotion because you are a Muslim. You complained about this discrimination to your supervisor’s boss—and when your supervisor found out, he called you a snitch and removed you from an important project as punishment. In this example, you would report the discrimination in Questions 13-15, and the retaliation in Part 2.

Part 2 / General advice: Part 2 of Form 11 starts with a section that discusses how the OSC views retaliation complaints. Read it carefully, because it’s a guide to being taken seriously. In particular, your complaint must cite every protected disclosure you made—and every retaliatory act that was linked to it. Dates, specifics, and supporting documents are crucial, which is why many whistleblowers keep a spreadsheet (see Pro Tip #1 above). Pay special attention to the list of “Covered Personnel Actions” in this section: Every retaliatory act that you cite must match at least one item from this list.

Note: Threatening one of these actions counts, too.

Part 2 then asks you to fill out a separate segment for each individual whistleblower disclosure. You should do these in chronological order, starting with your earliest disclosure. The more disclosures you can cite, the better.

Part 2 / List of disclosures and reprisals: For each disclosure, describe in full detail the possible wrongdoing or danger that you flagged. For instance, if you told your boss that you feared your department head might be receiving kickbacks, you should describe all the specific evidence that led you to this conclusion—and how and what, exactly, you told your boss. If you made the disclosure via e-mail, you should attach that document if it’s available. Label any attachments clearly, with titles that relate back to the disclosure. You don’t need to show that your disclosure turned out to be correct, and you don’t need to cite the specific law or rule that might have been broken. You just need to show that you reasonably believed there was some wrongdoing.

The form then asks specific questions about each disclosure. Let’s walk through each one:

PRO TIP #3

When providing a narrative—as you’ll do when describing your disclosures—it’s easy to veer off into tangents. Let’s say you were punished after disclosing to a higher-up that your boss admitted that he took a kickback. You might be tempted to add that you suspect that the boss bought his fancy new car with the proceeds. Your suspicion might be valid—but is it needed if the boss explicitly admitted his illegal action? The OSC prefers evidence to gossip. Keep your story 100% on point. After each draft, let it sit for 24 hours and then re-read it. If a detail doesn’t clearly advance your case, delete it.

Date of disclosure. Be as accurate as you can. If you have an e-mail with an exact date, that’s great. If all you can say is “Roughly Jan./Feb. 2019,” that’s OK too.

Person to whom you disclosed. This is crucial. Unless you called a hotline or something similar, you should be able to name an actual person.

Nature of wrongdoing. Hopefully it’s clear that you shouldn’t check “None of the above”—that would mean your disclosure is not protected by the WPA. You must check one or more of the other five boxes. Remember that you don’t need to have been correct, nor to have known what exact rule was being broken. The box(es) you check should broadly match your description of the disclosure.

Retaliatory action(s). The OSC is looking only for numbers here, corresponding to its list of “Covered Personnel Actions.” Again, threats count.

Date of retaliatory action(s). Once more, be as accurate as you can. Do not list a date that comes before your date of disclosure—that can’t have been retaliatory. If you are citing a series of disclosures that cumulatively led to at least one act of retaliation, then be clear about that. You will have a chance to explain further in Question 4 below.

As you cite each additional disclosure, you don’t need to repeat the same details over and over. If you described how you provided evidence of a kickback scheme in Disclosure A, then your description for Disclosure B might say, “Same as Disclosure A, except this time I provided a new piece of evidence and copied Allison Jones. The new evidence was …” It’s OK to list the same retaliatory action(s) for every disclosure you describe.

Part 2 / Question 3: As mentioned earlier in this guide, employees can face retaliation for whistleblower disclosures made by other people. The WPA also forbids this sort of retaliation, which is sometimes faced by the spouse of a whistleblower, or by a perceived friend of a whistleblower. It also can arise if a boss threatens to “punish the whole class” in the style of a frustrated high school teacher. If you’re in such a situation, you should provide the actual whistleblower’s details here, if known—and you may want to work with the whistleblower on completing the rest of Form 11, too.

Part 2 / Question 4: This may be the most important question on Form 11. Let’s assume that you’ve properly documented your protected disclosure, and you’ve shown that you suffered a personnel action. In order to get the OSC on board, you must show that there’s a connection between these two events. Think carefully and state your very best case.

Here are some factors you should consider:

Smoking gun. Did anyone tell you that you were punished specifically because of your disclosure? Was the person in a position to know? If you have e-mails or text messages that show someone credibly linking the events, or if you or another person can swear to the content of such a conversation, tell the OSC all those details.

PRO TIP #4

If you don’t have a smoking gun or proximity on your side, you may want to reconsider whether to file Form 11 by yourself—most especially if your agency has a credible-sounding explanation for your punishment. An experienced lawyer can help you to balance the risks and rewards of proceeding without legal help. If you’re represented by a union, you might consider filing a grievance instead.

Proximity. If you were punished soon after making a disclosure, an investigator is likely to conclude that the events were related. The longer a gap between the two events, the harder it’ll be to persuade the OSC without additional strong evidence. A gap of more than 12 months may be impossible to overcome without a smoking gun. Note: If you have multiple disclosures followed by a lone retaliation, consider focusing on your final disclosure—even if it wasn’t much different—as “the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Evidence of pretext. Was the official reason for your punishment obviously bogus? Have plenty of your peers done the same “bad” thing without any reprimand, or with a lesser punishment? Maybe you didn’t even do the “bad” thing—and you have witnesses who will support you? This can help to prove that you actually were punished for whistleblowing.

Punishment of others. Did any co-workers make similar disclosures—and, if so, were they targeted for retribution also? Was their punishment explained in a similarly pretextual way?

Violations of protocol. Did your agency skip steps when it punished you? For instance, did it skip oral or written warnings, or a performance improvement plan, if those are normally required for your alleged offense? If you were denied a promotion you had earned, did your agency fill the position without giving you a chance to apply? Such behavior can bolster your case.

Part 2 / Question 5 (remedy): As discussed earlier, the WPA says that you must be made “whole” if illegal retaliation is found—that is, you must be restored to the state you’d be in if the retaliation had never happened. When requesting a remedy, therefore, state clearly where you’d be without the retaliation, and why.

Would you be back in your old job? In a better job? In a different location? Ask explicitly for reinstatement, or promotion, or relocation—plus any back pay that you lost in the meantime. It’s good to state an exact job title you want, but you don’t need to give exact dollar figures.

If the retaliation hasn’t yet taken effect, the OSC may be able to put it on hold. Ask for that.

If you paid for legal advice while fighting retaliation—or if you expect to—ask to be reimbursed for that. If you had medical problems related to your punishment, caused by stress for instance, ask to be reimbursed for treatment. If you suffered serious emotional damage that can be confirmed by a professional, or possibly by your family and friends, ask for compensatory damages.

Less common: If you faced some public shame as a result of your punishment, you might ask for a rehabilitative statement to be made by your agency. You may not get it, but it won’t hurt to ask.

In short, don’t be frivolous in your proposed remedy—just assert your rights. Don’t get too attached to your proposals, however: Most OSC complaints end up being closed out with no remedy.

Part 3 (Consent): You must sign one (and only one) of the three “Consent Statements,” or else you’ll be deemed to have signed the least restrictive one. Read all of them carefully: They control whether OSC will communicate with your agency, and whether it can disclose your name to the agency.

The Employment Law Group advises most of our WPA clients to sign Consent Statement 1 if they’re serious about pursuing an OSC investigation, but it’s a personal decision for everyone. If you’re unwilling to sign anything except Consent Statement 3, then filing Form 11 may be a fruitless effort.

PRO TIP #5

As soon as you hit the button to file Form 11, set a calendar reminder for 120 days in the future. If the OSC hasn’t decided to take action by then, or if it has closed your case, that’s when you’re allowed to bring your complaint before the MSPB as an “individual right of action” (IRA). Is pursuing an IRA a good idea? It depends; see below. Note that your IRA will cover only the reprisal allegations you list in Part 2 of Form 11.

Part 4 (Certification): It’s right there on the form, but it bears repeating—lying or omitting material facts on Form 11 is a federal crime, so don’t do it.

Attachments: Attach all relevant, non-repetitive documentation of your protected disclosures; of your adverse personnel action; and of the link between those events. Attach copies only; keep any originals. Label every document clearly. The idea is to provide the OSC with enough evidence so that starting a serious investigation is a no-brainer.

After you click to “e-file” your complaint, you should be assigned a case number that starts with “MA.” Write it down and save/print out your full complaint.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT

Soon after filing your complaint you should receive a letter that includes your case number and the name of an OSC examiner assigned to your complaint. You are free to reach out to this person, and you can ask other people to send statements to the examiner. The examiner might call you, too.

Examiners are the OSC’s gatekeepers: They will look at your complaint, along with any supporting information, and choose one of three paths—closure, referral for mediation, or investigation for possible prosecution. (If you’ve asked for a stay, they may recommend that also.) You’d be surprised how many cases are closed at this early stage, often because the filer hasn’t submitted a complete and convincing complaint.

Be aware at this stage that the OSC examiner may reach out to your agency for a preliminary response—and, depending on the Consent Statement you signed, may disclose your identity. Many agencies have an official whose job is to coordinate with the OSC; this person should warn your superiors against retaliation. If you’re still in your job, however, take careful note of any unusual words or actions that are suddenly aimed at you.

The OSC examiner usually determines a course of action within 2-3 months of getting your complaint. Even if there’s no clear outcome by then, however, the OSC must provide you with a formal update at 90 days—and another update every 60 days after that, until there’s a final decision. Updates will arrive in writing via the U.S. Mail or e-mail, so watch your mailboxes carefully.

There are two main deadlines in this process:

- By 120 days after your complaint is filed, the OSC should have decided whether it’s pursuing your case via mediation or investigation. If it’s not pursuing your case (or if it hasn’t decided), you have the option of proceeding to the MSPB by yourself.

- By 240 days after your complaint is filed, the OSC should have completed its entire process—but if it’s not done, you can opt to give it an extension.

If the examiner decides not to pursue your complaint, you’ll get a “Preliminary Determination Letter” that notifies you and gives a brief explanation. This decision is not final, and you can respond with additional information within 13 days of the postmarked date on the notification letter. Even if you don’t have new information, we recommend that you respond by reiterating your case. A failure to respond may be seen as a withdrawal from the complaint process, which you don’t want. If the OSC still wants to close your complaint after you respond, it’ll send you a final determination letter that includes instructions on how to proceed to the MSPB. (See below for a discussion about going to the MSPB.)

If the examiner thinks your case has some merit, meanwhile, you may get referred to the OSC’s Alternative Dispute Resolution unit, which likely will offer to mediate the dispute with your agency. This is a common first stop for whistleblower retaliation complaints. You don’t have to agree to mediation; for more on that process, see below.

Finally, the examiner may decide that your complaint deserves some serious digging. In that case you’ll get a letter notifying you of a referral to the OSC’s Investigation and Prosecution Division—which then will have the remainder of the 240 days to take some action. As a first step in this process, you’ll usually get a phone call from the OSC investigator assigned to your case. Note that this is a different person than the initial examiner.

THE OSC INVESTIGATION PROCESS

The OSC investigator’s job is to figure out whether your complaint requires action—not to act as your advocate. The initial phone call will mostly be an introduction, but the investigator also will check if anything has changed since you filed the complaint. As with the examiner, you’re free to contact him or her as often as you’d like with extra information or follow-up questions.

While the investigator is looking into your matter, he or she may seek a stay of any punishment you’ve received. This mostly happens if you have strong evidence and suffered a severe harm, such as removal.

After reviewing all your materials, and possibly after talking with officials at your agency and any witnesses you have named, the investigator may contact you for extra information or documents—and, ultimately, will schedule a formal interview with you, probably over the phone. You should be as cooperative as possible.

At the end of the OSC’s substantive investigation, there are three big-picture possibilities.

First, the OSC may decide simply to close your complaint. In this case you’ll get a “Preliminary Determination Letter” as described above, along with the same option to respond and—assuming the decision doesn’t change—the same option to proceed to the MSPB.

PRO TIP #6

In our firm’s experience, the OSC promotes mediation after conducting a full investigation mostly in cases it’s unwilling to prosecute. If mediation fails at this point, therefore, your next stop will likely be the MSPB.

Second, if the OSC thinks your complaint is supported by at least some good evidence, it may try to settle the case informally. The investigator may reach out to your agency and push for a negotiated solution, for example, or he or she may suggest mediation. Again, see below for more on the OSC mediation process.

Or third, if the OSC thinks you have a strong case that won’t be (or wasn’t) settled informally, it may make a formal request for your agency to take corrective action—to reinstate you in your former position, for example, and to give you back pay. Agencies typically agree to such formal requests, but the OSC doesn’t have authority to force a resolution. If your agency balks, the OSC’s next step is to file a petition on your behalf with the MSPB, officially becoming your advocate in the case. Formal requests for action are rare, and OSC petitions to the MSPB are even rarer: The OSC takes on only a few such cases each year.

The OSC also may request disciplinary action against the person (or people) who retaliated against you. Again, since it can’t force such action, the OSC’s fallback is to petition the MSPB. While you wouldn’t be a party in that case, you might be called to testify.

Sometimes the OSC doesn’t complete its investigation phase within 240 days after your complaint. In such a case you’ll get a letter asking whether you want to keep going. We generally advise our clients to allow the OSC to complete its work—the alternative is moving to the MSPB or giving up.

The OSC may offer to mediate your dispute either before or after it has completed its investigation. Mediation is a voluntary process, so both parties must agree to take part. An OSC mediator typically will convene everyone in an office environment—maybe in adjacent conference rooms—and then, over the course of a day, try to find a resolution that’ll work for everyone.

(The OSC may offer other types of Alternative Dispute Resolution, or ADR, but mediation is easily the most common. Sometimes it’s done over the phone rather than in person.)

Should you agree to mediation with your department or agency? Every case is different, but our firm generally encourages it. Plus, as a practical matter, the OSC often ends up closing a complaint if the employee opts out of mediation—so really, there’s nothing to lose.

Will your agency agree to mediate? Probably yes. If your complaint hasn’t yet been investigated fully, a refusal to mediate will trigger a referral to the OSC’s Investigation and Prosecution Division. If the IPD investigation is already over, the OSC will likely close the complaint so you can proceed to the MSPB. Either way, it looks bad for a government agency to have rejected a step recommended by OSC.

Mediation is far less scary than a court date, and the mediator will likely be friendly to you, but your employer will likely be represented by an attorney. We believe it’s wise for you to lawyer up too, if only for the limited purpose of mediation. If you decide to go to mediation alone, however, please remember the following:

- Study all your documentation and evidence, so that you’re in command of all dates and facts

- Bring everything with you, organized neatly in binders so that it’s easy to access

- Don’t forget any proof of damages you have suffered—lower paychecks, mental health bills, etc.

- Dress professionally and don’t be intimidated by the other side

- Decide ahead of time what would force you to walk away, bearing in mind that your fallback (for better or worse) is the MSPB

- Don’t agree to a proposal unless it’s truly acceptable to you

- Be prepared for a long day

WHAT IF THE OSC CLOSES MY CASE?

If the OSC decides not to seek corrective action on your behalf, whether because it declined to investigate your complaint or because it investigated and went no further—or if you’ve chosen to opt out of the OSC process because it missed a deadline—the result is an individual right of action or IRA.

In short, an IRA is the right to appeal your agency’s retaliatory action to the MSPB, the governmental body that’s responsible for enforcing the rules of the federal civil service. You should have at least 60 days to file this appeal.

As a general rule, our firm doesn’t believe that federal employees should represent themselves before the MSPB. It functions much like a federal court and, in our experience, individuals have little hope of succeeding there without a competent, seasoned attorney. As a result, we’ll give only the briefest sketch of the process.

If you choose to move forward via an IRA, your appeal will be assigned to an administrative judge at the MSPB. The judge will issue an order that sets the schedule for your case. You’ll need to produce documents known as pleadings, and to attend a hearing. There won’t be a jury.

During your hearing, you’ll have an opportunity to call and examine witnesses—and to cross-examine any witnesses who testify against you. The judge may ask for closing arguments, or perhaps closing briefs, and later will issue a written decision. If you’re dissatisfied with the decision, you can ask for a review by the full MSPB—and if you don’t like that outcome, you can appeal it to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and beyond.

Is the IRA path worth pursuing? With an experienced federal employee lawyer at your side, perhaps, but it depends on the details of your case. At a minimum, many attorneys likely would be happy to review your OSC records and assess the strength of your claims—a reality check that would be worth your while, regardless of the result.

ABOUT THE EMPLOYMENT LAW GROUP

The Employment Law Group® law firm represents whistleblowers and other employees who stand up to wrongdoing in the workplace. Based in Washington, D.C., the firm takes cases nationwide.

APPENDIX

Flowchart of the OSC Process

The following flowchart is a simplified overview that shows the most

common outcomes and assumes that all deadlines are met.

The case was pursued by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Maryland

The case was pursued by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Maryland